Amid the pandemic, the logistics of grief change, but the emotional mechanisms remain the same

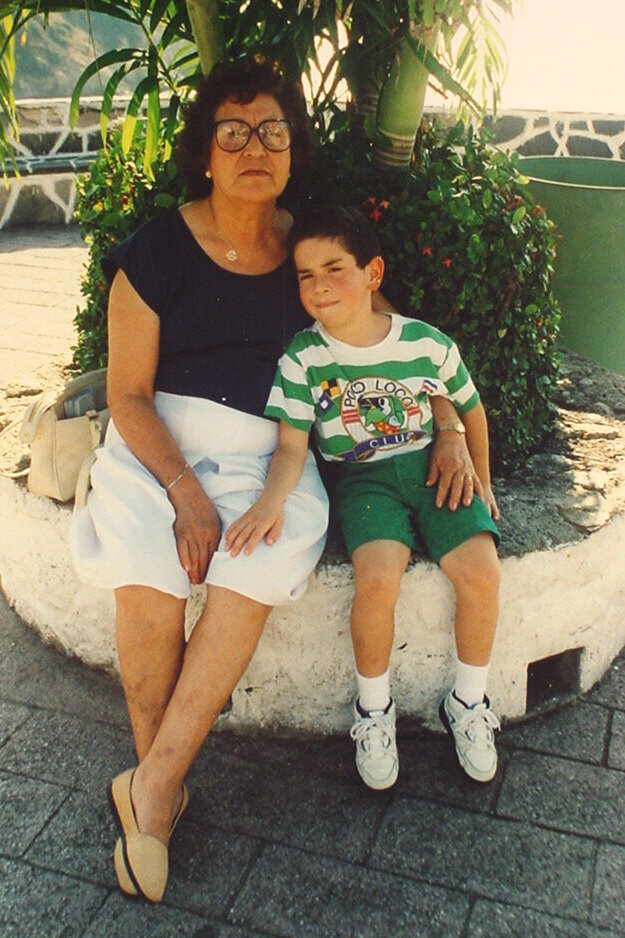

My grandmother and me in Acapulco in 1995.

Amid the pandemic, the logistics of grief change, but the emotional mechanisms remain the same

by GABRIEL CORTES | June 16, 2020

My family buried my grandmother last month on the day that coronavirus deaths in the United States crossed the 100,000 threshold. Her funeral was a small Catholic mass; only her four living children (including my mother) and their spouses attended. They sat in separate pews. The priest who led the service wore a face mask.

I watched the whole thing—the open-casket viewing and the service—on a webcast from the comfort of my apartment in St. Paul, Minn. 1,800 miles away.

I’m a native Californian, and I moved to Minnesota last August to join American Public Media as the Research Lab’s data journalist. I’m geographically far away from my family right now, but my parents and I talk on the phone almost every night, and, because of that, I was very aware that my grandmother’s health was declining. My mom kept me updated on my grandmother’s condition throughout the spring, and, as her health became more frail, I began contemplating what I would do when the time came.

My grandmother at her 50th wedding anniversary celebration in 2002.

Before the pandemic, I thought that videoing a funeral was not only macabre and distasteful, but downright vulgar. But when my grandmother died, and my mom told me the incredibly difficult decisions she was having to make about planning this very small service—I felt a responsibility to set my misgivings aside and watch the live stream.

It’s a decision hundreds of thousands of people in the U.S. have been making since state and local governments began imposing safer-at-home orders earlier this year.

California was at the vanguard of that movement: San Francisco Mayor London Breed declared a state of emergency for the Bay Area in late February—the first city leader in the U.S. to do so—and issued stay-at-home orders shortly thereafter. Los Angeles and the rest of the state quickly followed suit.

The restrictions came down hard and fast: All nonessential businesses were shuttered, and social gatherings—including funerals—were limited to 10 people. Some places, like Los Angeles County, limited funeral services even further, stipulating that the 10 people in attendance had to “live together at the same physical address.”

Keisha Licea coordinates funeral services at Thomas Miller Mortuary in Corona, Calif., and helped plan my grandmother’s funeral. She said that attendance was originally capped at 250 mourners, which seemed manageable.

“They went down to 10, and it was just crazy,” Licea said. “You could only have 10 people in the room at one time and you had to clean in between.”

That cleaning and disinfecting protocol was labor intensive and impractical, so she and the other mortuary staff got creative. The rules only applied to individuals coming into the mortuary facility, so the staff installed a loudspeaker in the parking lot to accommodate drive-thru services. In one instance, they set up an urn with flowers and pictures of the deceased so that mourners could express their condolences from their cars, Licea said.

“Families would drive through; friends would drive through,” she said. “They would say a few words, and things like that; you know, wave, give flowers and drive on. So they weren’t coming into our facility.”

The drive-thru service is a novel solution to social distancing restrictions, but the biggest change to funeral services has been the wide-spread adoption of the webcast.

“When we announced that we were going to do the live streaming, people thought it was very cold,” Licea said, “They just thought that, ‘You know what, that's just not the way to go.’”

My grandmother and me at her home in California in 2017.

But the longer the restrictions from the pandemic have gone on—from weeks to months—Licea has seen the initial objections to broadcasting funerals turn to acceptance. The tide has changed.

“We’ve gotten lots of comments from family saying that they do appreciate that we were able to allow, you know, 50 to 60 other relatives to see their loved one,” she said.

At one funeral, more than 250 people watched the webcast from across the country. The company that hosts Thomas Miller’s live streams called to alert them that the service had been a new record for the mortuary’s viewership, Licea said.

The adoption—and acceptance—of virtual funerals is happening across the country. Robinson Funeral Homes in Easley, South Carolina operates three chapels and one cemetery. They’ve hosted several online services with hundreds of viewers, director Chris Robinson said. At one virtual funeral, the online audience almost reached 700.

The guidelines for funerals in South Carolina were not strict as they were in California; Robinson said he and his staff followed guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that capped attendance at 50 people. Even so, they quickly upgraded the cameras that they had in their chapels to high-definition when restrictions went into effect.

“Occasionally, we would have a request,” Robinson said about web-streaming funerals before the pandemic. “The demand was nothing like it is now.”

For many families mourning their dead during the pandemic, they had no choice but to accept the virtual funeral: They could either watch the service on the web or not attend at all. But that stark reality didn’t make it any less uncomfortable, including for my family.

We’re Mexican Catholics; we’re used to very large funerals. My grandmother had countless relations—grandchildren, siblings, nieces and nephews, and so many other extended family—who, were it not for social distancing orders, would have been present to mourn her.

My Great-Uncle Johnny poses with the image of my grandmother broadcast before the webcast of her funeral began.

My Great-Uncle Juan Serrato (my grandmother’s younger brother) was one of them. And like me, Uncle Johnny watched my grandmother’s service on a screen.

“It was very sad,” Uncle Johnny told me in Spanish. “I was sad that I couldn’t be there with my sister.”

But Johnny and his family innovated. His son set up a television on his back patio and invited Johnny’s other children and their families to come over and watch the service together.

“In the end, it was like I was there,” Johnny said. “I saw her. I saw everyone. And it was better than not being there at all.”

Johnny’s matter-of-fact acceptance of the webcast surprised me, but Keisha Licea of Thomas Miller Mortuary and Chris Robinson of Robinson Funeral homes both agreed that this trend will continue even as social distancing restrictions are lifted.

“People will still be afraid to come out,” Licea said. “Maybe they have underlying causes or other things like that, that will keep them from wanting to be in large crowds.”

The lifting of restrictions may soon be a moot point, however. Of the more than 1.3 million people who have died in the U.S. this year, nearly 10% have died from COVID-19, according to CDC. As death counts continue to rise, some states, like Oregon, have halted their phased reopenings.

For my part, watching my grandmother’s funeral alone in my apartment was one of the most surreal experiences of my life: It was heartbreaking, but, it was also humbling and, ultimately, spiritually edifying. I have never felt so far away from my family and so close to them at the same time. And despite my initial unease, I am so very grateful that I could (kind of) be there.

I still think it’s a weird concept, but, like Uncle Johnny said, it’s better than not being there at all.

Esperanza Serrato—my grandmother—was born in 1929 in a small, rural town in Michoacan, Mexico. When she was still a girl, her family moved north to the desert state of Sonora, and while coming of age there, she formally studied pattern-making and sewing.

My grandmother adjusts the wedding dress she made for her daughter Ortensia in 1974.

She became an incredibly talented seamstress, and she maintained her sewing skills all her life. Sitting at her non-electric, pedal-powered Singer, my grandmother was as comfortable altering simple hems (she was still hemming my pants when she was well into her 80s) as she was designing and executing detailed wedding gowns (which she did for two of her daughters).

She married my grandfather in 1952 and immigrated to the U.S. in 1961. They raised six children, four of whom survive her. She is also survived by 10 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

My grandmother was stoic, hard working, prudent, and, above all else, generous—four of the most cherished qualities for a Mexican woman of her generation. She died of natural causes a month shy of her 91st birthday.